-

About COVID-19

COVID-19 is an illness that is caused by a new coronavirus called SARS-CoV-2. Coronaviruses also cause colds and more serious illnesses (SARS and MERS).

-

Is COVID-19 man-made?

Other coronaviruses (SARS and MERS) jumped from animals to people. Researchers are investigating the origin of the virus. Although they are not sure which animal SARS-CoV-2 came from, they have found a virus in bats that is over 96% similar to the human form.

-

How is COVID-19 transmitted?

SARS-CoV-2 is passed in tiny particles that are too small to see.

These tiny particles enter the air when someone who has COVID-19 lets out their breath, talks, sings, sneezes or coughs. When another person inhales these particles, or if they land in a person’s eyes, nose or mouth, they can become infected. This is called aerosolised transmission.

It is possible – but much, much less likely – that someone could become ill with COVID-19 if they touch their eyes, nose or mouth after touching something that has tiny particles of the virus on it.

-

How can it be prevented?

Many people who have COVID-19 do not have any symptoms – but they can still transmit the virus.

For this reason, it is important to assume that anyone could have it, not just people who are ill.

-

COVID-19 can be prevented by...

- Keeping at least 1.5 metres away from other people, which is called ‘social distancing’.

- Wearing a mask that covers your nose and mouth.

- Avoiding crowds – especially when indoors.

- Keeping windows open when you are inside to get fresh air flowing.

- Limiting the number of people that you spend time with and socialising outdoors.

- Washing your hands for at least 20 seconds many times a day. use soap and water or hand sanitiser that is at least 70% alcohol.

- Avoiding unnecessary visits to clinics or hospitals.

- Calling or going to your health centre if you have a fever and it is hard for you to breathe.

- Staying home and away from other people if you feel ill.

- Getting vaccinated

- Sunlight, wind and the outdoors are your friends. For example, although there is still some risk to eating at a restaurant, it is much safer to eat at an outdoor table than one inside, where airflow is not as good.

-

Testing for COVID-19

There are different types of tests for COVID-19.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests are sent away to a lab.

Lateral flow tests (LFT) can diagnose someone immediately, but are not as accurate as PCR tests.

Samples are taken with a swab inserted into the nose.

In South Africa, COVID-19 testing is recommended for anyone with symptoms. If you need to be tested for COVID-19, speak with a healthcare professional who can order a test for you.

Public sector testing for COVID-19 is free. If you are using a private laboratory, check for coverage and cost.

-

What happens to people who have COVID-19?

COVID-19 is unpredictable. Nearly half of all people who have it don’t have any symptoms. Many people have a mild illness that they recover from completely.

For people who do develop symptoms, they begin 2 to 14 days after getting COVID-19.

-

COVID-19 symptoms include...

- Fever

- Chills

- Dry cough

- Shortness of breath

- Difficulty breathing

- Appetite loss

- Fatigue

- Muscle or body aches

- Headache

- New loss of taste or smell

- Sore throat

- Congestion or runny nose

- Nausea or vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Skin rash

- Red or purplish fingers or toes

- Conjunctivitis (red, itchy eyes that may be crusty when you wake up)

Some people remain ill for months, with “long COVID” and/or have permanent lung, heart or brain damage and loss of smell and taste.

Because COVID-19 is a new illness, researchers are still learning about it and working to figure out what causes long-term symptoms – and how to treat people who are having them.

COVID-19 can also cause severe illness and death. The risk for serious illness is higher for people over age 65 years and/or people with other conditions, including diabetes, high blood pressure, tuberculosis, obesity, and a weak immune system.

Although people living with HIV are not more likely to get COVID-19 than other people, they may be likely to fall seriously ill, especially if they have a low CD4 cell count and/or are not taking HIV treatment.

-

Is there treatment for COVID-19?

Most people will recover by themselves at home, while self-isolating to prevent COVID-19 from spreading. Fever can be treated with paracetamol. People who are taking medicine for asthma, hypertension, diabetes, HIV or other conditions should continue taking it.

Researchers are studying many treatments for COVID-19. Dexamethasone, a steroid, is recommended for seriously ill people with COVID-19. But only if they are in the hospital receiving oxygen or on a ventilator (a machine that helps people who cannot breathe on their own).

-

About viruses & variants

After a virus enters a person’s body, it copies itself. Viruses can make millions or billions of copies each day. Some of these copies may have changes, which are called mutations. Mutations can weaken viruses, making it harder for them to survive – or they can make viruses contagious and/or more deadly.

The more people who have a virus, the more chances the virus has to mutate. SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, has infected over 100 million people in just one year, giving it many opportunities to mutate.

A group of viruses with the same mutations is called a variant. There are already many coronavirus variants.

In South Africa, the coronavirus variant 501Y.V2 – now called the Delta variant –was discovered during December of 2020. This variant has mutations that make it more contagious, and a mutation that helps the virus to hide from antibodies.

This means that people who have already had an older version of the virus can get re-infected with the variant, and that some of the coronavirus vaccines based on older versions of SARS-CoV-2 are less effective against this variant.

-

The immune system: about antibodies

When viruses and other invaders, called pathogens, enter the body, the immune system works in different ways to stop them from making a person fall ill.

One way the immune system responds to pathogens is by making Y-shaped proteins called antibodies.

Each pathogen has a specific antigen – like a sign with the name of a business – on its outside. Antibodies are custom made to recognise and stick to each specific antigen, just as people will visit a barber shop for a haircut.

Vaccines also trigger the immune system to make antibodies (see About Vaccines). It takes a few weeks for the immune system to make antibodies. After a person has already made antibodies to a specific pathogen, the immune system recognises it and goes into action quickly.

-

How do antibodies work?

Antibodies stick to a specific antigen. They work in different ways to stop people from falling ill. Some of them, called neutralising antibodies, stop pathogens from getting inside of cells.

Other antibodies cover pathogens with a sticky coat to stop them from working or mark them so that other immune system cells to find and destroy.

-

Do antibodies always protect people?

Antibodies protect people against many viruses, such as polio, hepatitis B and the flu.

They always fight pathogens, but sometimes they cannot defeat them, such as with HIV.

Also, viruses can change so much that antibodies do not recognise them, so they cannot fight them.

Read more about this in the section “About Viruses and Variants”.

-

How long do antibodies last?

It depends on the person and the illness. Some people produce weak antibodies, or very few of them. This happens for different reasons: the immune system gets weaker as we age; HIV and other conditions may also weaken it, as do certain medicines used to suppress the immune system.

Antibodies to some illnesses, such as measles, can last for decades, while others only last for a few months. Since COVID-19 is new, researchers are still learning about it. So far, we know that they can last for six to eight months in some people.

There are new vaccines for COVID-19. We are still learning about how long they protect people. It is likely that people will need annual boosters. For more information, look at the section “About Viruses and Variants”.

-

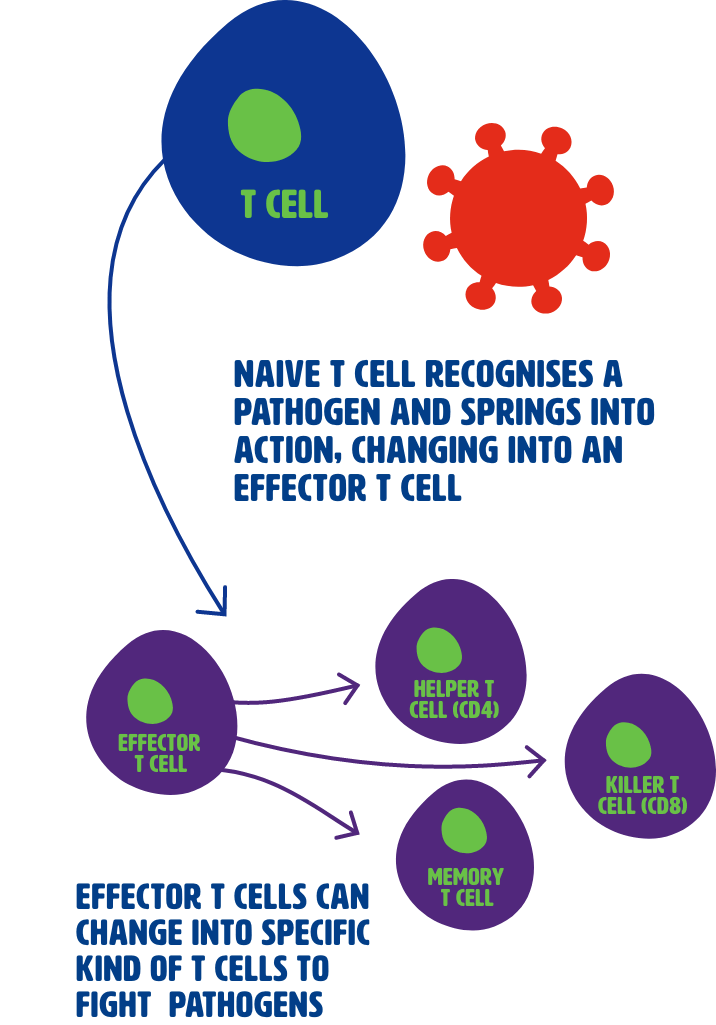

About T Cells

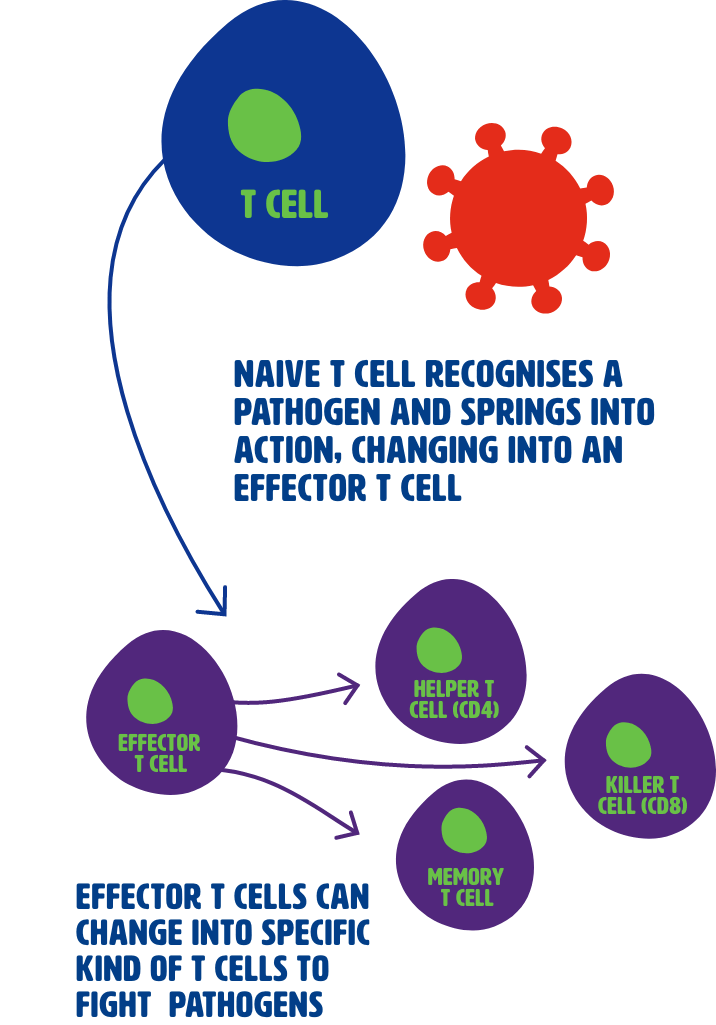

T cells are white blood cells that are part of the immune system.

T cells can recognise a specific pathogen when they see a fragment of it on the outside of infected cells.

-

How do t cells work?

T cells that have not seen a pathogen are called naive T cells. When naive T cells recognise a fragment of a specific pathogen, it triggers them into action, and they become effector T cells.

Effector T cells work in different ways to fight pathogens. The helper T cells (also called CD4 cells) send signals to, and coordinate other immune system cells to respond to invaders, while killer T cells (also called CD8 cells) can recognise and kill cells that are infected with a pathogen. After they have done their job, most effector T cells die. A small group of them, called memory T cells, will survive.

-

Do T cells always protect people?

T cells cannot always protect people. Some people are born with immune deficiencies, or they may need to take medications that suppress their immune system, such as after an organ transplant. Also, untreated HIV destroys T cells, leaving people vulnerable to infections.

-

How long do T cells last?

Memory T cells, which recognise a specific pathogen, live for years after the body has fought it off. They respond when the same pathogen re-enters the body and trigger a rapid immune response.

-

About vaccines

Vaccines work by triggering the immune response to a harmless version of, or a piece of an antigen – just like your own immune system does when an invader enters it.

A vaccine introduces a new antigen to the immune system without making people sick, triggering B cells to make antibodies.

When vaccinated cells die, they leave spike proteins and pieces of other proteins in the bloodstream.

Another part of the immune system, called antigen-presenting cells, sweeps up these spike proteins and fragments from the bloodstream.

Antigen-presenting cells display these bits of coronavirus proteins on their surface, where helper T cells and killer T cells can recognise them.

Helper T cells coordinate the immune response, telling B cells to make antibodies.

At the same time, killer T cells find cells that are infected with coronavirus – and destroy them.

-

Vaccine side effects

Vaccines have side effects, which are caused when the immune system reacts to them. This confuses people, who think that the vaccine has made them sick. But it really means that the vaccine is working.

These side effects, which are usually mild, can include:

- Fever

- Pain or swelling near the injection side

- Chills

- Aching muscles and joints

- Feeling tired

- Nausea/vomiting

Some people have a severe allergic reaction to vaccines, but this is very rare and can be treated. It is important to let health care workers know if you have ever had a severe allergic reaction, or if you have allergy symptoms after getting a vaccine.

Allergic reactions are different to and far less common than side effects.

-

How the COVID-19 vaccine works

Just as there are different ways to meet people (websites, through friends or a matchmaker, at bars or parties), vaccines have different ways of introducing antigens to the immune system.

No matter how coronavirus vaccines work, they are all aimed at the same target: a part of the coronavirus called spike protein which sticks out from the virus.

The coronavirus uses its spike protein to enter our cells. It fits into the ACE-2 receptor, which is a protein on the outside of cells found throughout the body. The spike protein fits into the ACE-2 receptor the same way that a key fits into a lock.

The main idea behind vaccines is to bring a harmless version of the coronavirus to the immune system. Once the immune system sees spike proteins, it makes antibodies that stop the spike proteins from entering cells, the same way as when the real virus enters your body.

Coronaviruses vaccines work by triggering helper T cells, which coordinate the immune response, including telling B cells to make antibodies, and by triggering killer T cells, which destroy coronavirus-infected cells, and:

- By delivering a coronavirus treated with heat, radiation or chemicals, so it cannot make you ill – this is called an inactivated vaccine.

- By using a weakened form of the coronavirus that cannot make you ill – this is called a live-attenuated vaccine.

- By bringing instructions directly to your cells, so that they make their own spike proteins- without the rest of the coronavirus – this is called the genetic approach.

- By using an inactive virus (called a vector) that cannot not make you ill as an envelope to deliver the coronavirus to the immune system – this is called a viral vector vaccine.

- By using parts of the coronavirus that the immune system needs to recognise – this is called a subunit vaccine.

-

Keep going!

Well done on completing this Learn More section!

Keen to keep learning? Check out these sections next.